Start date: 01-02-2020

End date: 01-08-2020

Clinical problem

Hearing loss is the second most prevalent (>440 million people affected) health impairment worldwide, with adequate diagnosis and treatment lacking for many. In case of severe or profound hearing impairment, rehabilitation can be provided by a cochlear implant (CI) that directly stimulates the auditory nerve via acoustically modulated electrical current pulses. The CI provides auditory sensations, and in the most successful cases leads to near-normal speech perception in low-noise listening conditions. However, not all CI recipients experience such a successful outcome; the variability in speech perception outcome among CI recipients is large. Moreover, under noisy listening conditions, CI performance is poor for all recipients.

Binaural hearing, which is essential for speech reception in noisy conditions, is currently missing in CI recipients. Only one implant is reimbursed for adults, effectively leading to only monaural restoration. Evidence however suggests that two ears are necessarily better. Still, recipients with two CI devices (bilateral CI recipients) have poor sound localization abilities. In practice, even bilateral CIs are fitted per side and do not account for potential bilateral effects of the implant.

When the performance of the CI recipient is sub-optimal, it is often not clear whether improvements are possible. Due to the vast parameter space that controls the cochlear implant, finding the optimal settings for the CI recipient is time-consuming for both patient and clinic, vary with local expertise, and can only include a small subset of parameters during the limited testing time.

Previous research showed that machine learning models can localize sound based on binaural data under normal or distorted listening conditions. Following this line of research, we will check the biological plausibility of the binaural processing strategy in artificial neural networks. The final goal is to find a plausible model to simulate binaural hearing under perturbed listening conditions, which will then act as a simulation tool for optimizing the parameter space of CIs.

Solution

Successful completion of this project will result in an improved emulated processing strategy which can provide valuable improvements and innovations for actual CI recipients to achieve binaural hearing. The foreseen technology will improve the quality of life of CI recipients by allowing them to participate in more everyday activities in noisy environments.

Research Question

Is the azimuthal sound localization strategy of binaural neural networks biologically plausible, such that we can use them as simulation tools for CI coding strategies?

Methods

Data

We artificially created bandpass filtered gaussian noise samples with different loudness and convolved them with head-related transfer functions (HRTFs) to provide the model with the same binaural cues that are available to humans. Additionally, we transformed the input of each ear to the frequency domain before providing the sound to the neural network. The Azimuth angle of the HRTF was used as training label. A separate test set was created to evaluate the models.

Models

We have tested many models with different configurations on their exploitation of the interaural level differences to predict the location of the provided sound. The following 5 models symbolize the steady progression of our analyses.

Model 1: A fully connected neural network with one hidden layer consisting of 2 hidden nodes with sigmoid activation functions, trained only with HRTFs with zero elevation. This is the simplest model we could come up with to get a lower bound baseline.

Model 2: A fully connected neural network with one hidden layer consisting of 2 hidden nodes with sigmoid activation functions, trained on all HRTFs. Here, we wanted to establish a baseline for azimuth localization of elevated sources.

Model 3: A fully connected neural network with one hidden layer consisting of 20 hidden nodes with sigmoid activation functions, trained on all HRTFs. This network is similar to earlier research regarding neural networks in binaural hearing.

Model 4 Early Fusion: A fully connected neural network with two hidden layers consisting of 40 and 4 hidden nodes with LeakyReLU and Sigmoid activation functions. This network was designed to attempt the split of spatial tuning and frequency tuning found in biological neural networks.

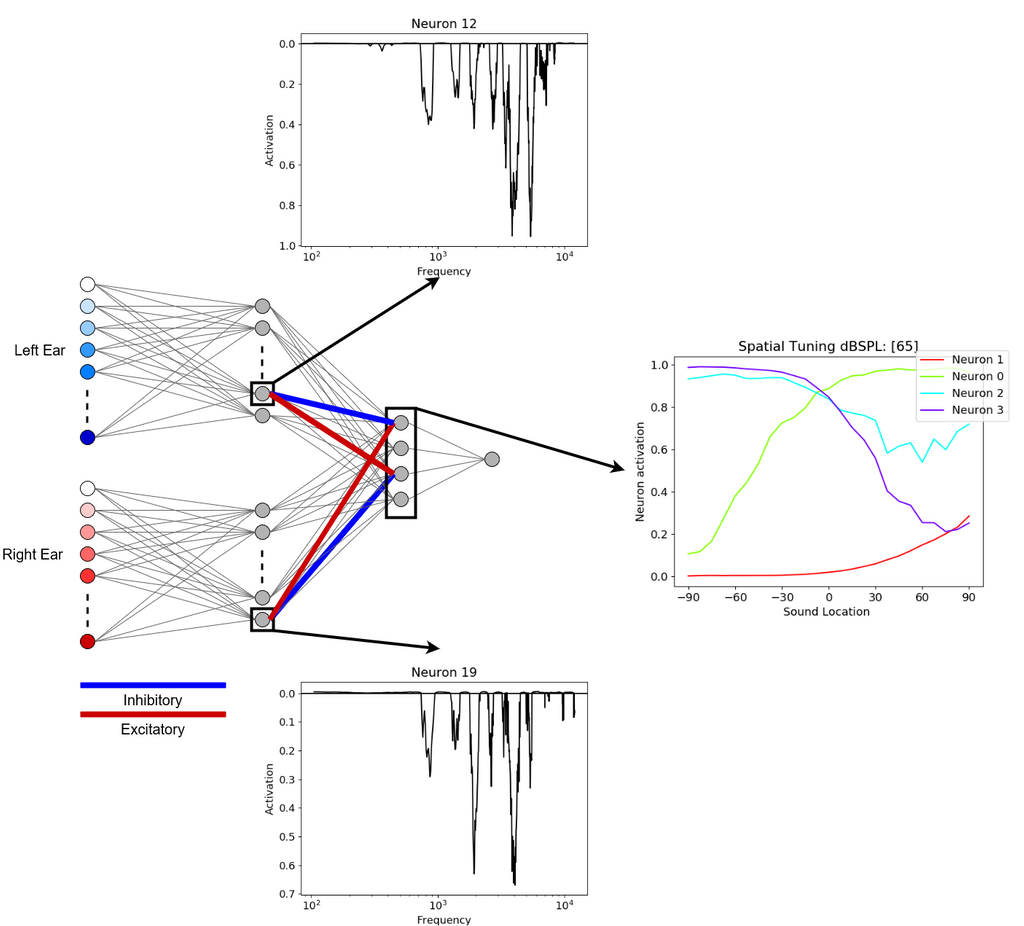

Model 5 Late Fusion: A late fusion neural network, where the inputs of the two ears first get processed by their own hidden layers of which each has 20 hidden neurons and LeakyReLU activation functions, before they get combined in the second hidden layer consisting out of 4 hidden nodes with Sigmoid activation functions. This network was a continuation of Model 4, but with an extra monaural processing layer. The idea was inspired by the extra synapse at the anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN) between the auditory nerve and the lateral superior olive (LSO).

Experiments

For each model, three analysis steps were conducted. First the localization performance was tested in the typical stimulus response graphs also used in human experiments. Additionally, we evaluated the frequency and spatial tuning of each of the neurons in the neural network. From animal studies we know that neurons in the LSO are spatially broadly tuned to their respective hemisphere, also called opponent coding, and only respond to a sharply tuned narrow frequency band.

Results

| Model | Localization Error | Localization Accuracy | Frequency Tuning | Spatial Tuning |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | 5° | 1.0 | Sharp | Sigmoidal Opponent Coding |

| Model 1 | 6.4° | 1.01 | Broad | Sigmoidal Opponent Coding |

| Model 2 | 6.6° | 0.98 | Broad | One Hemisphere |

| Model 3 | 5.1° | 0.96 | Broad | Broad |

| Model 4 | 3.2° | 0.99 | Broad | Linear Opponent Coding |

| Model 5 | 4.1° | 1.01 | Multi Band | Sigmoidal Opponent Coding |

Model 5 Frequency Specific Interaural Level Comparison

In the first monaural hidden layer are neurons 12 and 19 tuned to the same frequencies of the left and right ear respectively. In the second hidden layer neurons 0 and 3 show the characteristic sigmoidal spatial tuning curves, coding for the right and left hemisphere. The spatial tuning curves can be explained by a frequency specific comparison with inhibitory connections from the contralateral side and excitatory connections from the ipsilateral side. Specifically, neuron 0, coding for the right hemisphere, receives inhibitory input from the left ear (contralateral) and excitatory input from the right ear (ipsilateral). The opposite is true for neuron 3, coding for the left hemisphere, receiving excitatory input from the left ear (ipsilateral) and inhibitory input from the right ear (contralateral).

Conclusion

This project has tried to validate the biological plausibility of binaural neural networks with the goal of using these networks as simulations of binaural hearing to improve the coding strategy of cochlear implants. The most striking result is that almost any architecture can achieve human level performance in estimating the azimuth location in the conventional stimulus response measures. Still, after opening the black box of binaural neural networks we can see a wide variety of localization strategies whereof none can be seen as fully biological plausible. Despite our utmost efforts in complicating the standard HRTF-convolved noise stimuli, i.e. presenting different loudness levels, filtering various frequency bands & including elevated sound locations, the neural network developed its own localization strategy which never was sharply tuned in frequency. The most promising model we found is Model 5, whose neurons are still tuned to multiple frequencies but only within a certain bandwidth. Still, this model is the only model that showed signs of using frequency specific binaural level comparison to localize sounds.

Having gained these novel insights in the localization strategy of binaural neural networks, there are two trajectories future research could explore. First, by using the available simple CI-preprocessing pipeline and analyzing the differences of the localizing strategy to the "normal hearing Model 5", we might find necessary features that vanish through the CI-preprocessing. For example, in Model 5 we saw the importance of frequency specific binaural level comparison. Common CI-processing strategies such as the independent acting automatic gain control severely distort the underlying binaural level differences, or in the case of the N of M channel strategy, completely remove binaurally matching frequency bands.

Second, rethinking the stimulus creation and task the neural network has to solve. Currently, the stimuli for training and testing of the networks are both bandpass filtered gaussian noise. Despite noise being also used for testing human sound localization, the human auditory system has been "trained" with wide range of stimuli, under different circumstances and with various tasks. Regarding the stimuli, our auditory system has to deal with tones, voices or animal vocalizations, all of which have different spectral compositions which are currently not mimicked by the simple bandpass filtering of noise. Additionally, humans localize sounds within different environments with background noise, such as looking for a friend during a concert, or when we take a group picture in front of a waterfall. Moreover, the human auditory system is adapted to distinguish pitches. We can for example distinguish between the cashier asking us to pay and a child asking whether it can get some chocolate. Training the neural network to localize more complex stimuli over background noise while also identifying the pitch might provide the necessary complexity to force the neural networks to employ a more human like localization strategy.

The code and final report of this project can be found here.