Start date: 16-11-2020

End date: 16-05-2021

Clinical problem

Early this year, during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals in hard-hit regions were overflowing with patients presenting at the emergency unit with respiratory complaints. To diagnose COVID-19, a positive RT-PCR test would be needed. But there was a huge shortage of tests and when swabs were made for RT-PCR, the result of the test was often only received after several days. This was a problem, since a physician would like to decide in a few minutes whether to send a patient home for self-isolation or hospitalize him or her, and if so, send him or her to a COVID-19 ward or a regular ward.

To quickly obtain a working diagnosis, many hospitals decided to make chest CT scans of all COVID-19 suspects arriving at their emergency room.

Several Dutch hospitals collaborated and produced a standardized system for reporting these CT scans called CO-RADS. Radboudumc validated CO-RADS and showed in a Radiology publication that in this high prevalence situation predicting whether patients had COVID-19 on the basis of the CT scan alone could be done with high accuracy (area under the ROC curve of 0.95).

Subsequently, researchers from the Diagnostic Image Analysis Group together with colleagues from Amsterdam and Bremen, developed an AI system to perform this diagnosis and they showed in another Radiology publication that the AI system, called CORADS-AI and publicly available on https://grand-challenge.org/algorithms/corads-ai/, was nearly as accurate as radiologists in making this assessment. However, during the first peak of the pandemic, the population of COVID-19 suspects suffered from few other diseases that mimic the appearance of COVID-19, for example other pneumonias (during the COVID-19 peak, the yearly influenza peak had already passed) and other interstitial lung diseases. As CORADS-AI was trained with only scans from Radboudumc obtained during the peak of the pandemic in 2020, we expect that CORADS-AI may perform a lot worse during the upcoming winter season.

Meanwhile, it has become evident that certain laboratory tests from blood are also quite predictive for COVID-19. These blood tests can also provide results within minutes. It is clear that an optimal test would analyze both the CT scan, clinical parameters and blood test results.

Solution

We want to improve CORADS-AI by training it to differentiate between COVID-19 and other lung diseases and by combining the CT scan analysis with routinely acquired blood parameters. This improved CORADS-AI system can then be used during the upcoming winter season and maybe it could even do a background screening of any patient who undergoes a chest CT scan in the hospital, flagging suspect cases to the technician who acquires the scan while the patient is still in the room. Patients with a suspicious scan could then receive an RT-PCR test immediately.

Data

We have access to several public and proprietary data sets of CT scans, clinical information and blood test results. In total, scans and clinical features of thousands of COVID-19 suspects and people without COVID-19 who were examined in the pre-COVID-19 era, are available.

Approach

Roel will be supervised by DIAG researchers who contributed to CORADS-AI and he will have access to Sol, a high-performance deep learning cluster. There are several machine learning approaches that could be explored to differentiate between COVID-19 and other lung diseases with overlapping patterns and to combine CT scans with clinical features and blood values.

Project results

Methods

This project looked at several methods to improve upon CORADS-AI, by incorporating additional information such as clinical values and sex and age of the patient. Specifically, we used CORADS-AI as a visual feature extractor by running it on each chest CT scan and extracting the activations in the last layer of the network. These visual features were then concatenated to the clinical features and the resulting vector was used to train gradient boosting decision tree (GBDT) models.

In addition, we realized that missingness plays an important role in clinical feature datasets, and thus we developed methods to analyze and mitigate this effect to obtain fairer evaluations and increase model generalizability. Specifically, we trained models to predict COVID-19 based only on missingness information in order to determine the extent to which missingness is predictive for COVID-19.

We also implemented and designed several methods to mitigate fitting on missingness in clinical feature datasets. Firstly, we looked at imputation techniques. Specifically, we looked at mean, k-NN, and MiCE imputation. Secondly, we developed a technique based on SHAP values to remove the contributions of missing features on model output, which we called SHAP zeroing. Thirdly, we employed an ensembled multiple imputation approach (MI and MI TT) which utilizes random column-based sampling to impute data many times. Each of these datasets would then be used to train models and construct a voting ensemble. Finally, we developed a custom decision tree implementation (DT) designed to reduce fitting on missingness.

We evaluated all of these methods on three datasets; we looked at data from Radboud (henceforth referred to as RUMC), the integrative CT images and CFs for COVID-19 (iCTCF) dataset, as well as a dataset based on data from CWZ and Radboud (henceforth referred to as just CWZ). The latter two contain data from two hospitals (Union and Liyuan for iCTCF, and Radboudumc and CWZ for the CWZ dataset), and thus we also evaluated all models in a cross-hospital manner: training on data from one hospital and evaluating on data from the other.

Results

The following table shows the performance of the various approaches we tried in terms of AUC for non-cross-hospital prediction. Each cell shows both the AUC achieved when using only clinical features, as well as when using a combination of clinical and visual features. Additionally, the top row shows the performance of CORADS-AI. For CORADS-AI, only one AUC is shown, as this model only operates on chest CT scans, and not clinical features. The best AUCs are shown in bold.

| CWZ | iCTCF | RUMC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CORADS-AI | NA; 0.800 | NA; 0.761 | NA: 0.464 |

| Imputation: KNN5, GBDT | 0.858; 0.844 | 0.823; 0.854 | 0.792; 0.732 |

| Imputation: MEAN, GBDT | 0.862; 0.836 | 0.925; 0.895 | 0.794; 0.782 |

| Imputation: MICE, GBDT | 0.870; 0.852 | 0.773; 0.836 | 0.754; 0.790 |

| Base, GBDT | 0.870; 0.836 | 0.940; 0.899 | 0.859; 0.835 |

| Optimized, GBDT | 0.884; 0.849 | 0.961; 0.902 | 0.911; 0.859 |

| SHAP zeroing, GBDT | 0.862; 0.841 | 0.908; 0.861 | 0.883; 0.843 |

| SHAP zeroing optimized, GBDT | 0.868; 0.874 | 0.939; 0.812 | 0.889; 0.865 |

| MI, GBDT | 0.827; 0.806 | 0.760; 0.799 | 0.780; 0.770 |

As you can see in this table, the GBDT models work quite well when provided only clinical features, outperforming CORADS-AI. When the model is provided visual features as well, the performance generally decreases. All of the missingness mitigation approaches generally yielded worse performance, suggesting that missingness may be important in predicting COVID-19 for such GBDT models.

We also evaluated all models for cross-hospital prediction. The following table shows the performance of the various approaches we tried in terms of AUC for cross-hospital prediction. Each column label is of the format "training data->test data". Each cell shows both the AUC achieved when using only clinical features, as well as when using a combination of clinical and visual features. Additionally, the top row shows the performance of CORADS-AI. For CORADS-AI, only one AUC is shown, as this model only operates on chest CT scans, and not clinical features. The best AUCs are shown in bold.

| RUMC->CWZ | CWZ->RUMC | Union->Liyuan | Liyuan->Union | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORADS-AI | NA; 0.885 | NA; 0.826 | NA; 0.812 | NA; 0.854 |

| Imputation: KNN5, GBDT | 0.842; 0.846 | 0.743; 0.848 | 0.666; 0.842 | 0.613; 0.772 |

| Imputation: MEAN, GBDT | 0.862; 0.857 | 0.697; 0.845 | 0.713; 0.875 | 0.640; 0.787 |

| Imputation: MICE, GBDT | 0.873; 0.855 | 0.694; 0.826 | 0.519; 0.879 | 0.624; 0.726 |

| Base, GBDT | 0.858; 0.840 | 0.725; 0.807 | 0.761; 0.864 | 0.717; 0.730 |

| Optimized, GBDT | 0.886; 0.838 | 0.751; 0.808 | 0.577; 0.848 | 0.680; 0.734 |

| SHAP zeroing, GBDT | 0.860; 0.846 | 0.776; 0.860 | 0.644; 0.849 | 0.711; 0.777 |

| SHAP zeroing optimized, GBDT | 0.893; 0.863 | 0.809; 0.867 | 0.525; 0.889 | 0.670; 0.760 |

| MI, GBDT | 0.874; 0.854 | 0.756; 0.840 | 0.643; 0.863 | 0.667; 0.868 |

Performance is generally worse here than in non-cross-hospital prediction. When the model is provided visual features as well, the performance is generally improved in this case. The missingness mitigation approaches failed to yield reliably improved performance, suggesting that fitting on missingness is not the main factor leading to reduced performance in cross-hospital prediction.

We also trained models to predict COVID-19 based on missingness instead of the underlying feature values (i.e. only Booleans indicating whether a value was measured or not were provided to the classifier, but none of the data that was actually measured). The table below shows the results of that evaluation. Each cell shows both the AUC achieved when using only clinical features, as well as when using a combination of clinical and visual features. The best AUCs are shown in bold.

| Model | CWZ | iCTCF | RUMC |

|---|---|---|---|

| BaggedGBDT | 0.667; 0.666 | 0.954; 0.955 | 0.879; 0.885 |

| GBDT | 0.702; 0.702 | 0.932; 0.942 | 0.863; 0.863 |

| LR | 0.634; 0.633 | 0.943; 0.944 | 0.853; 0.853 |

It seems that for both iCTCF and RUMC, missingness is very predictive of COVID-19, as well as to a lesser extent in CWZ.

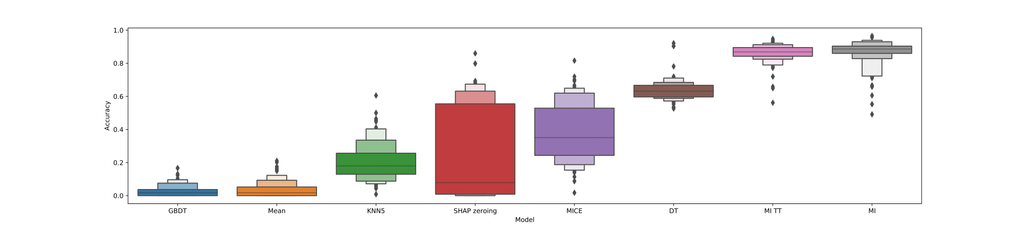

In order to evaluate the four different methods we used to mitigate fitting on missingness, we employed a random data augmentation strategy. We performed 100 of such augmentations and computed accuracy scores for various (versions) of these missingness mitigation methods. The results of this are shown in the following boxplot:

As you can see in this boxplot, the base GBDT model performs very poorly on this task (worse-than-random), whereas the custom decision tree implementation and ensembled multiple imputation generally lead to better-than-random performance. This suggests that these two techniques are indeed effective at mitigating fitting on missingness.

Conclusions

In this thesis, we investigated whether chest CT scans can be combined with clinical features to achieve better performance in predicting COVID-19 PCR outcomes and diagnoses than either modality on its own. Based on our experiments, this does indeed seem to be the case for most datasets and train/test splits, as long as both data modalities are of sufficient quality.

Furthermore, we discovered that which values were measured in hospitals is often very predictive of COVID-19 PCR outcome/diagnosis, suggesting that models may sometimes utilize this information rather than the numerical clinical values themselves. Going forward, such issues should be taken into account when working with clinical data like this, as this may compromise generalizability and result in skewed representations of model performance. Indeed, it would seem that there is little value in a model whose predictions are merely reflections of an expert's verdict, embedded in the data by way of missingness. Therefore, the various techniques we presented in this thesis may be beneficial in mitigating these problems and obtaining fairer representations of model performance and generalizability.

Regardless of these issues, we do believe that some of the models developed in this thesis could be clinically useful in detecting COVID-19, as well as being used for COVID-19 screening. Furthermore, the methodologies we employed could be employed for related clinical problems.

In the future, the methods we developed can be used to improve how this kind of research is conducted and evaluated, resulting in more reliable clinical machine learning models. Additionally, the methodologies we presented here may be expanded upon further in a variety of ways, which could aid future clinical and non-clinical research alike.

Full thesis

The full thesis can be found here.

Code

The code developed as part of this thesis can be found here.